What proportion of funds under management should be allocated to startups?

Despite generous support for angel investment by governments such as those of the UK and South Africa, investment has not been forthcoming. Based on the KPMG study cited above, 47,000 entrepreneurs received seed capital globally between 2010 and 2016 – less than €60 billion. Since there are 750 million entrepreneurs in the world and 9% are expected to be high expectation entrepreneurs, with the top 2% creating between 25% and 30% of net new jobs, we assume that only the top 2% should be allocated funding and the Aziza Coin will only focus on this section of the market. The chances of an adult being a high expectation entrepreneur and receiving seed capital funding in any given year is close to 1 in a million.12

Based on a population of 750 million entrepreneurs in the world, The Top 2% that “deserve” seed capital represents a population of 15 million. As these 15 million entrepreneurs are at different stages of their business development, only a small proportion will require seed capital each year. We assume that this population of entrepreneurs will be replaced every ten years, with successful exited businesses being replaced by young hungry start-ups. We assume that the stock of “Top 2% “start-ups turns over every three decades. This means that 500,000 entrepreneurs should be funded each year.

Every generation – defined as 30 years – this top 2% cohort is replaced with an up and coming cohort. Therefore, if the entire top 2% is to be funded over the 30 year period, 500,000 entrepreneurs around the world need to be allocated seed funding. In 2016 only 6,147 of them received seed funding. We therefore estimate that a mere 1.2% of the potential market is being served. Remarkably, the top 2% can be identified solely on the size of the business they intend to create at the point of start-up.

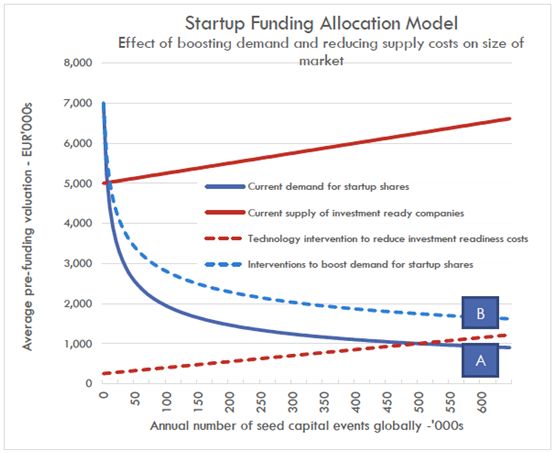

In terms of levels of capital requiring to be deployed per seed capital investment, we assume that the seed investment capital requirement will reduce as the population increases. Currently, the median pre-investment valuation in start-ups is €5 million, and the median investment at €0.7 million. We assume that if it were to increase to the target level, significant economies of scale will result in material savings in the amounts needed for starting up – see examples in Securitisation of the Central Services Contract. We therefore use €250,000 per start-up investment in our theoretical model.

Based on 500,000 entrepreneurs per year and seed capital of €250,000, we therefore estimate that €125 billion per year should be allocated. The following stylised demand and supply curve shows how the market can grow. The Aziza Coin Foundation’s intentions will reduce the cost of supplying investment ready start-up shares and increase investor demand for them. This would reduce the price of investment and increase the number of investments, and the size of the market.

The above figure shows how transaction costs force up the required valuation for a start-up funding event to happen. Start-up deals cost more in management time than buying assets in larger businesses, because they are so fraught with risks larger businesses avoid. Interestingly, this model shows that increasing demand for start-up shares will have little impact on the number of deals. The market for seed capital was €8 billion in 2016, where 6,147 deals were funded at a median pre-funding valuation of €5.1 million. As the graph above shows, increasing demand to curve B from curve A will have little effect, the issue of bridging the funding gap lies firstly with reducing the cost of creating an investment ready start-up. If it is possible to reduce the pre-funding valuation required to €1 million – an 80% reduction, with the €250k initial investment, the global target of supplying €125 billion per annum in seed capital will indeed be possible.

Counter intuitively, this requires a new type of large organisation that can drive down the cost of providing the services start-ups need by an order of magnitude. This new type of organisation will require substantial economies of scale to make this model sustainable. The Aziza Coin Foundation plans to create a replicated model, starting in South Africa.

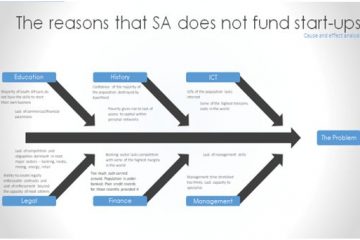

Within the current South African context, Total Entrepreneurial Activity has improved marginally from 5.4% in 2004 to 6.9% in 2016. This is less than 50% of the benchmark for other middle-income countries where the TEA sits at 15%. With the country’s adult population growth, the number of entrepreneurs has increased from 1.7 million to 2.5 million over this period. This means that the “Top 2%” comprises 50,000 owner-managed businesses that created over a quarter of the net new jobs the economy created. According to the venture capital association, only 44 businesses were funded in 2016, and none of these were start-ups. South Africa is not alone among developing economies – start-up funding simply does not exist, but the effects are particularly cruel with the country’s history. It is not difficult to see how this market failure has contributed to the country’s 36% unemployment rate. Applying this logic to the South African economy offers promising results. If there are 50,000 fundable businesses that are funded at a rate of 3.3% or 1,660 per year, with an average investment of €150 000 (R2.5 million) which represents 60% of the model’s global average, the start-up sector would receive €250m per year or €1 billion over the next four years. This is about 0.4% of the R4.7 trillion of funds currently under management.

0 Comments